“Why are you leaving so early today for your school?” my mother asked; I must have been 17 then.

“Ammi, I have to go to school, lead the procession of my house from my school to the Gurudwara. If I won’t go, who will guide and sing Gurbani the whole way?”

The last two years of my school life were spent at Sri Guru Nanak Higher Secondary School, a famous school in Ramgarh, Jharkhand. It was my first peek into Punjabi and (more accurately) Sikh culture. Always being surrounded by diverse cultures at school allowed me a new perspective towards an inclusive society, breeding a sense of mutual love and admiration for people from a different religion.

The highlight in our school year was Guru Nanak Jayanti or Gurupurab, a time when the entire school would get a makeover, with decorations adorning every part. A Langar procession was led from our school singing Hymns along the way, to the Gurudwara. All the Sikh kids would wear the same coloured Turban and non-Sikhs would wear a similar yellow-coloured patka (bandana) along with our white school uniform. The sight of a few hundred similar coloured head coverings always brightened up the surroundings.

I distinctly remember hearing the recitation of Gurbani a couple of days before the celebration and learnt that this is known as Akhand Path, which is an uninterrupted non-stop complete reading of the Guru Granth Sahib. This Path is practised at times of hardship or joy. The entire atmosphere at school seemed more calming at this time.

Before I share more, it is imperative we pause to talk about Langar, Guru Nanak’s Gurupurab and Gurbani.

Gurpurab celebrates the birth of the first Sikh Guru, Guru Nanak, who laid the foundation of Sikhism and is thus one of the most important festivals for Sikhs. It is celebrated all over the world with a spiritual fervour. Celebrations are generally spread over three days with devotees visiting Gurdwaras, seeking Guru Granth Sahib’s blessings, eating and participating in the langar, and decorating their homes with lights. The day serves as a reminder to devotees to follow the teachings of the Gurus and live a life true to Nanak’s philosophy of Oneness.

Langar itself finds an origin in Persian and literally translates as ‘an almshouse’ or ‘a place for the poor and needy’, and is popular as the community kitchen in the Sikh tradition. The tradition of food offerings much like Langar can be found in traces across Sufi movements, Buddhist traditions and some Hindu temples (although each had some caveats). The Sikh concept of Langar is to provide food to everyone irrespective of any social stigma; hence it is not just charitable food but a movement to tear down perceived differences between classes and communities (a difference that was commonplace at the time).

Guru Nanak refreshingly believed in social service beyond just good intentions, he thought of it as imperative to spiritual awakening. A man without the bare necessity of food would obviously never be able to search for a higher meaning. Hence all the inspirations of community kitchens found a larger proliferation through Guru Nanak’s method of Langar. He attempted to put forth a value of Divinity in the community serving, and consumption of food. Moreover, it became a characteristic of the Sikh value system going forward, institutionalising the practice of community service.

One of the greatest teachings of the Guru was to work and care for others selflessly. It is this teaching that finds strength and can be seen manifested during occurrences both of distress and joy. This concept of feeding everyone (devotees and beyond) evolved to be Langar, and subsequently, the Sewa offered in the process is considered as the highest form of devotion.

Through Langar, one learns how to treat everyone the same and celebrate equality with love or utmost tenderness. This feeling of serving God by serving others is an ancient phenomenon. As someone who loves to cook and feed others, I am fascinated by the story of a young Guru Nanak.

It is said that Nanak’s father gave him money to perform a Sacha Sauda and make some profit out of it. Nanak went around town to invest and earn some profit but he was not able to zero down on anything. Then he saw holy men who were suffering from hunger. He decided that providing food to them was a worthy cause to invest in and earn blessings and perform Sacha Sauda. When he returned home, he was reprimanded for wasting the money, yet Nanak unequivocally stated that feeding the needy was the best use of the money he could imagine and he could not fathom any other way.

The langar consists of simple vegetarian food like sabzi, daal, roti, rice and sweets. You can also find an unlimited supply of tea in a few Gurudwaras specially Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar (Golden Temple) where you can enjoy it, sitting in a designated area while listening to Gurbani which is broadcasted through speakers. The relationship between Gurbani and Guru ka Langar is evident and symbiotic.

When our school Gurupurab procession reached the destination – our local Gurudwara, we washed our hands and walked in through the pool of water meant to cleanse our feet. We quietly murmured our respective prayers in front of the Granth, bowed down, humbly receiving the blessings. Students proceeded to eat Langar but a few kids like me were more excited to do Sewa and picked up the vessels to serve everyone sitting in the Langar hall. I picked up the dal; the smell was divine – cooked with fresh local and unadulterated ghee. They say the taste of a delicious meal lies in simplicity and a Langar meal proves it right. We are instructed to not to waste any food while serving, we are instructed to bend down and serve every morsel onto the plate avoiding any spillage in the process; this mindfulness gives value to the food as well as the person eating. It is not just about serving communal food but also serving it with dignity.

Another memorable moment of exploring Langar came along in 2019. While I was shooting in Amritsar, I decided to do Sewa in the kitchen at the Golden Temple and took a tour of the gigantic kitchen there. It was a beautiful experience which words can’t justify.

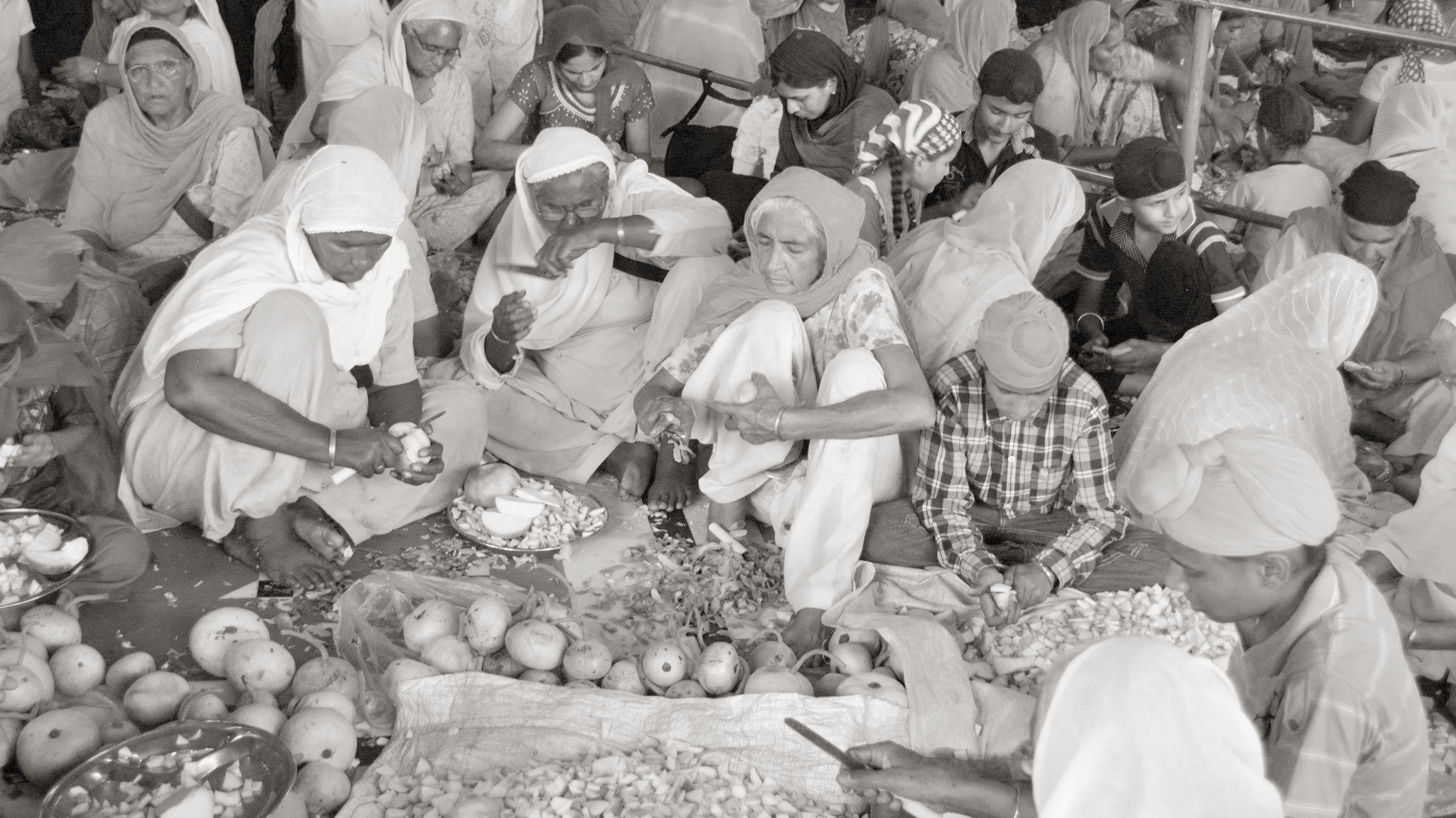

The Sewa kitchen was huge enough to accommodate more than 200 persons, all of whom sat in an assembly line, rolling the rotis (mostly women) whereas the men were sitting next to the stove baking the rotis.

Irrespective of religion, caste or community, you could partake in Sewa; two things are a prerequisite though – clean hands and clean intention.

The Langar at the Golden Temple is herculean, serving upto 50,000 people a day! On holidays or religious occasions, the number often goes up to 100,000! You may do any kind of Sewa – from chopping, cooking, cleaning, serving or any other task that takes your fancy (as long it aids the Langar process). As I was shooting my co-host urged me to roll the rotis the ladies started giggling assuming I won’t be able to roll perfectly round rotis, of course little did they know that I cook for a living. Needless to say, they were surprised to see my rotis and then made me roll five more (else I’d stay single forever, they proclaimed). Before I moved away from the ladies, they made me promise that when I get married I will bring my partner to this Gurudwara and to take blessings of the Guru. I could not say no to them.

This was a peek into two amazing years of my life spent at Guru Nanak Higher Secondary School followed by scattered experiences of community and communion. At school, I started going to the Gurudwara (a practice that continues till today) and one would often find me there. Moreover, as time passed and I found myself in Delhi, the tradition of celebrating Gurupurub or going to Gurudwara has also continued.

Some things have remained constant from Ramgarh to Delhi to Amritsar – the simplicity of food and ghee laden Kada Prasad.

Today we observe that the tradition of Langar has continued to cross borders, not only showcasing the charity of the Sikh community or the country but also the selflessness in practice. It is evident that devotion is found in serving the Guru, by serving the people.