What are symbols and what is their impact on society? Surely, there are positive symbols as well as negative ones. How must we distinguish one from another, and what truly is the value of symbols in religious practice?

Many such questions today evoke in us conundrums that we find challenging to easily comprehend. Yet we must face these questions with fortitude and engage with them to find viable answers. To work towards better answering such questions, we must build our understanding of the concept of symbols and how they interact in Sikh culture and religiosity.

“If the Sikh today rank as best farmer, a dogged soldier, a dedicated administrator, a sure man at the machine, truck driver of unbounded stamina, and on the whole, an untiring worker in every field of activity, it is on account of the habit of loyalty which he has imbibed through the discipline of Keshas through generations’’

Most of us express our identities through the clothes we wear or articles we put on. Especially, in religions across the world one sees such an embodying of one’s faith through articles and such symbols; whether it is the ‘Kippah’ that Jewish men wear, the ‘Purdah’ some Muslim women have on or simply a locket with a cross that some Catholics chose to carry. We often tend to understand them as simply reiterations of larger communal beliefs and belonging that has been continuing for centuries but we must also acknowledge the context of their origin and their significance today.

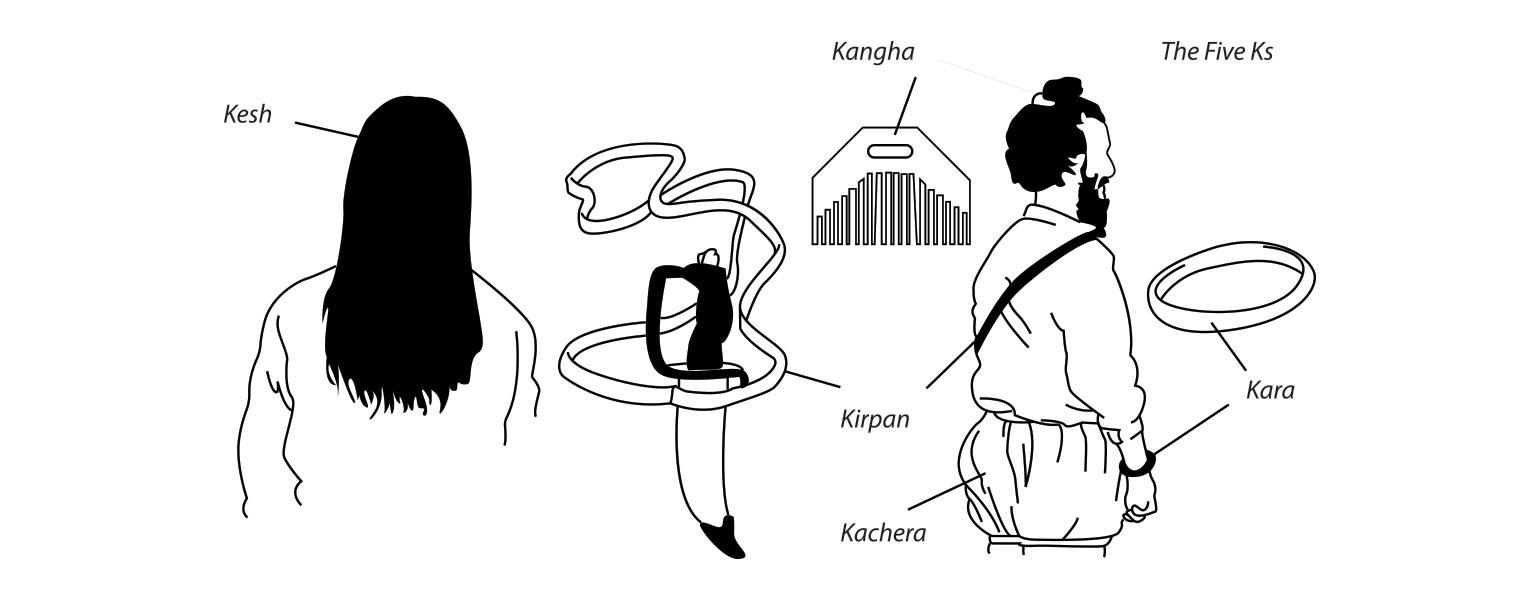

In Sikhism as well, articles of faith have been prescribed for both men and women. Known as the 5K’s, they are Kesh, Kanga, Kara, Kachhera, and Kirpan. These symbolic articles have great metaphysical inspiration.

The Kirpan, for example, symbolises a Sikh’s obligation to fight tyranny.

The Kanga, a reminder of always remaining an active and useful member of society and not renouncing the world.

The Kara, a positive and world affirming sign.

The Kacchera, a symbol of self-consciousness and control.

The Kesha, a practice of loyalty and belief in the Supreme.

While some have a context of struggle and survival, some also have a context of purely philosophical principles Sikhs wish to uphold today. One is expected to follow an outer code of conduct that blends in with the inner discipline, Atma ki Rehat (code for the soul).

Today, in the practice of Sikhi, we are witnessing a shift towards the inclination of worshipping the photos of Gurus instead of praying and reciting verses from the Sri Guru Granth Sahib. There is also a fall in men and women adhering to the prescribed code of conduct (whether it is the keeping of Kesh, tying the turban, or wearing the Kirpan) as we all struggle to ‘blend in’ into an environment that continues to grow apprehensive about distinctness.

Whether it is looking different, by tying a turban and keeping a beard or whether it is practicing mindfulness in the invigorating space of a Gurudwara – this month’s issue wishes to reassess and engage with the changing, and the extremely personal, relationships individuals have shared with these articles and spaces.

Some questions it wishes to prod – How have these personally affected us in our everyday as we stepped out into the world and what have they meant to us?

As we literally embody centuries-old concepts and ideologies how do we negotiate and contextualize the continuing relevance of these principles to larger ideas of belonging and civic responsibility.

“ The argument that symbols are no longer necessary in a peaceful society because, in such society, the organisational strength itself is rendered redundant is based on an unrealistic hypothesis: that social condition remains static. Since social conditions never remain static, the potential of the organisational strength has to be maintained to match the change in circumstances. Woe Befalls a country which, having emerged from a war into conditions of peace, disbands its army and allows the quality of its fighting forces to deteriorate. Similarly, a society of individuals pursuing certain spiritual aims, and maintaining an organisation for the defence of one’s right to pursue these aims, fares badly if it dispenses with that organisation because divesting itself of the potential for its defence, it prepares itself-Chamberlain like- to make compromises affecting the spiritual ideals themselves.”

Professor Kulraj Singh

In this edition we make our foray into addressing symbols from various perspectives as well as beginning a discourse on how we must evolve with them. We must find inspiration in the metaphysical value that it allows us to extract and channel our energy through this understanding of the symbols of faith.